Environmental Inequality in Cancer Alley and Across America

Yellow rain and dead birds. That’s some of what you’ll find in the 85-mile stretch of land along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans dubbed ‘Cancer Alley.’

But the Louisiana River Parishes (what would be counties in other states) along Cancer Alley are home to the U.S.’ highest concentration of two other things: petrochemical plants and refineries, and cancer mortality rates.

How did things get so bad? It boils down to environmental blackmail and racism. And while Louisiana’s Cancer Alley is one of the most blatant examples of environmental inequality in America, it’s not the only one.

Today, as concerns over the impact of environmental inequality increase, we’ll put the spotlight on the groups who have been protecting their communities for decades. We’ll dig into what grassroots groups have accomplished in Louisiana’s River Parishes and other communities across the country.

Environmental Blackmail and the False Promise of Prosperity

As of 2017, Louisiana was home to 320 manufacturing and processing facilities that are required to report their toxic releases to the EPA. But these plants weren’t always here. The story of how these processing plants came to Cancer Alley is a familiar one, where economic growth is prioritized over the health, wealth, and well-being of communities of color and those experiencing poverty.

In the mid-to-late 20th century, Southern states like Louisiana were ardently embracing industrialization. States saw industrialization as a way to lift their chronically impoverished populations into the prosperous American middle class that was in its heyday throughout much of America. Louisiana offered corporations huge incentives to build their facilities in the state. In many cases, residents eagerly welcomed these plants as well.

An American Tale as Old as Time

Profits and the promise of economic growth have always been placed before the health, safety, and livelihood of communities of color in America. Many Black residents of Louisiana’s River Parishes and their families have lived in the area for centuries. Many of their ancestors were brought to America as slaves, forced to toil in brutal conditions, and emancipated into a life of sharecropping before facing decades and decades of further discrimination. Cancer Alley is simply the next chapter of that abuse.

Pulling the Rug Out From Black Communities

When it came time to build, things took a turn for the worse. Just like how highways were being built over and through Black and other communities of color in American cities, petrochemical processing companies built their toxic plants in vulnerable communities that hoped to benefit from the business.

Manufacturers have argued that the economic benefits outweigh the damage it does to the environment. However, residents living in these ‘sacrifice zones’ don’t actually see significant benefits from these facilities.

New builds and expansions often came with the promise of well-paying jobs, but that promise never materialized. After all, local employees would be concerned about the pollution, but employees commuting in and out of town? Not so much.

According to a survey taken by one town along Cancer Alley, St. Gabriel, just 9% of residents worked in the local facilities. Meanwhile, every person in these communities experiences the full brunt of the environmental and ecological impacts.

Today, the cost of economic growth and the empty promises of the past are on full display in Cancer Alley. There, the poverty rate is nearly 19%, well exceeding the national average. Likewise, the cancer prevalence is nearly double the national average.

Change Came From Within

In the latter half of the 20th century, as petrochemical plants sprouted like mushrooms, something else was happening. The communities that had been neglected were mobilizing. They were organizing and developing the skills and tactics to prevent and oppose further violations of their rights.

Marginalized communities in Louisiana river parishes—and across America—were sowing the seeds that grassroots environmental movements would continue to sprout from, even up to our present day.

An example of this organizing came in the Iberville Parish in the early 1990s. There, residents on the Mississippi River’s West Bank felt disenfranchised and ignored by their local government. They had little say over what new facilities could be built in their neighborhoods. Enough was enough. In 1994, they took action and incorporated the city of St. Gabriel to secure political power over their own community.

In the nearly 30 years since incorporation, St. Gabriel hasn’t approved any new facilities in their jurisdiction. While the nature of air pollution doesn’t protect St. Gabriel from facilities outside the city limits, it’s an inspiring example of a community taking charge and confronting the issues that deeply impact its residents.

The Work in Cancer Alley Continues, Despite Corporate Opposition

Moves to incorporate since St. Gabriel did so have been less successful due to well-funded opposition from corporations. However, that doesn’t mean the environmental justice movement in Louisiana’s river parishes hasn’t made progress.

RISE St. James, a group opposing similar facilities in the St. James Parish, scored two massive victories in late 2022. They successfully blocked the construction of two petrochemical plants that would have emitted a total exceeding 15 million tons of greenhouse gasses each year.

It’s one victory, but Louisiana residents aren’t going away. And they shouldn’t have to—it’s their home. Groups like the Louisiana Bucket Brigade have served as a strong, action-driven ally for Louisiana’s fenceline communities—those directly neighboring chemical facilities—since 2000. In the decades since they’ve worked with towns and neighborhoods in the areas most impacted by pollution.

CCHD supports groups like the Louisiana Bucket Brigade because by partnering with communities to amplify their voices, we can help communities challenge the petrochemical industry’s relentless expansion, and promote environmental justice.

Communities Across America Organize to Protect the Environment

As we’ve established, the environmental movement doesn’t have a single frontline. While the egregiousness of Cancer Alley has garnered national and international headlines, Low-income communities and communities of color across America are organizing to oppose and overcome the challenges facing their communities.

Fair Corporate Taxation and Environmental Justice in Tennessee

In the early 1970s, activists in Eastern Tennessee organized against mining businesses that exploited the local land and weren’t being fairly taxed. The group, Save Our Cumberland Mountains, has since evolved to support Black communities across the entire state, operating under the name Statewide Organizing for Community eMpowerment.

Over the last 50 years, SOCM and its members have contributed to campaigns that have stopped the construction of toxic waste incinerators, mountaintop strip-mining operations, and other developments that would adversely impact the health of their communities.

CCHD is proud to support organizations like SOCM that work to protect land and defend the dignity of all Tennesseans.

Protecting Children’s Health in Baltimore

In Baltimore, a city trash incinerator burns as much as 2,250 tons of garbage each day and expels an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide. The pollutants from such incinerators can lead to respiratory illnesses and even make their way into the bloodstream due to their microscopic scale. Students in the area were rightfully alarmed to learn that the city was planning to build a newer and larger incinerator less than a mile from two schools.

By collaborating and organizing with the United Workers Association (UWA), a formerly-CCHD-funded group, students led a successful campaign against the construction of the new incinerator.

Organizing for Lead-Free Water in Milwaukee

In Milwaukee, the CCHD supports the Milwaukee Intercity Churches Allied for Hope, which has co-founded the Coalition on Lead Emergency, or COLE. COLE has helped create a program for lead abatement workers and pass an ordinance that punishes landlords who don’t remove lead hazards from their property.

Be an Agent of Change in Your Community

Environmental injustice and discrimination aren’t limited to Louisiana, Tennessee, Baltimore, or Milwaukee. It’s happening in Portland, Flint, Los Angeles, and cities all around the country. While environmental injustices can seem daunting, they can be overcome. Like the communities in Louisiana, Baltimore, Milwaukee, and more have demonstrated, it just takes dedication and perseverance.

CCHD has been supporting these communities for half a century. We know that while this work is crucial, it takes resources that are hard to come by in areas that have been disenfranchised over time. By supporting community-driven, grassroots groups, we can help enable communities to determine their own futures, protect their families, and create a better world one city at a time.

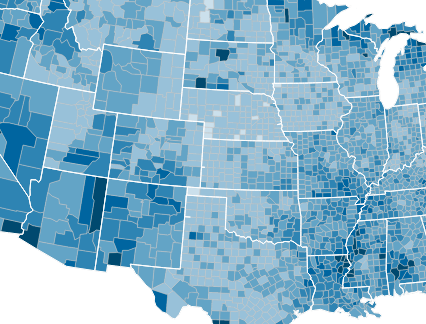

To connect with your local CCHD-supported groups, check out our map displaying dozens of incredible, community-focused groups across the country. If you can’t get involved in your community, consider supporting the CCHD National Collection in November, If you missed the collection, or your (arch)diocese doesn’t participate, you can support the collection online with #iGiveCatholicTogether.

Finally, help us elevate our work for environmental justice across the United States by sharing this article and connecting with us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram!

About CCHD

The Catholic Campaign for Human Development (CCHD) was established by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops to carry out Jesus’ mission, "...to bring glad tidings to the poor...liberty to captives...sight to the blind, and let the oppressed go free" (Luke 4:18).

CCHD follows two main objectives. First, to help low-income people and those experiencing poverty participate in decisions that affect their lives, their families, and communities. Secondly, we seek to educate and enhance the public’s understanding of poverty, its root causes, and the systems that allow it to persist.

To learn more, check out our educational resources or encounter stories of hope.